Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco Author, Alia Volz, opens up about what it was like to grow up with parents who made medical marijuana history.

Alia Volz is the author of the new memoir Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020), winner of the Golden Poppy Award for Nonfiction from the California Independent Bookseller Alliance and finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Autobiography.

She’s a homegrown San Franciscan. Her work has been published in The Best American Essays, The New York Times, Bon Appetit, Salon, and The Best Women’s Travel Writing. Her family story has been featured on Snap Judgement, Criminal, and NPR’s Fresh Air.

Alia has received fellowships from MacDowell and the Ucross Foundation and has twice been awarded the Oakley Hall Memorial Scholarship from the Squaw Valley Community of Writers.

However, Alia didn’t grow up like the average kid – she grew up with parents who believed in the magic of cannabis edibles, long before it was cool, and way before it was legal.

We caught up with Alia in advance of the release of the paperback version of her book, Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco, on 4/20. Learn more about Alia, her upbringing, and how her story is important to cannabis history by reading our interview below.

High Herstory. Your mom, Meridy, began Sticky Fingers Brownies: a cannabis edibles business that boomed during the 70s and 80s, when weed was much more illicit, and definitely not regulated. What did her business risks teach you about going after your own career dreams?

Alia Volz: My mom is one of the hardest-working people you’ll encounter. She makes her own luck. I don’t like to use the word “manifestation,” because this isn’t about dreaming or meditating something into existence. It’s about determination, hustle, bold moves, and creative thinking. If the infrastructure doesn’t exist for what my mom wants to do, she builds it herself. She became a cannabusiness pioneer by not letting anyone else dictate what she could or couldn’t do.

These are invaluable lessons for an author. Writers will hear “no” fifty times before a publisher says “yes.” It’s a career with few opportunities for success and many pitfalls. You have to build your own support system, work insane hours for little pay, and not let rejection blow you off course. Then, there are rare and wonderful moments when you can survey your progress and realize you’ve accomplished the impossible.

At one point, the family business was moving about 2,800 brownies per week. Did your family face any criminal penalties or scares during this time?

They never got busted, fortunately. There were close calls, like when undercover narcs sniffed around my mom’s customers in the Castro, but they managed to slide under the radar. I attribute this to a smart business model. The Sticky Fingers Brownies salespeople each developed delivery route through a particular neighborhood. Rather than selling to strangers on the street, they catered to regulars on the job—people who worked in cafes, boutiques, medical offices, florists, etc. Most customers bought dozens every week—and then distributed them through their own social circles. The brownies circulated widely, but very few people knew where they came from. The cops never figured it out.

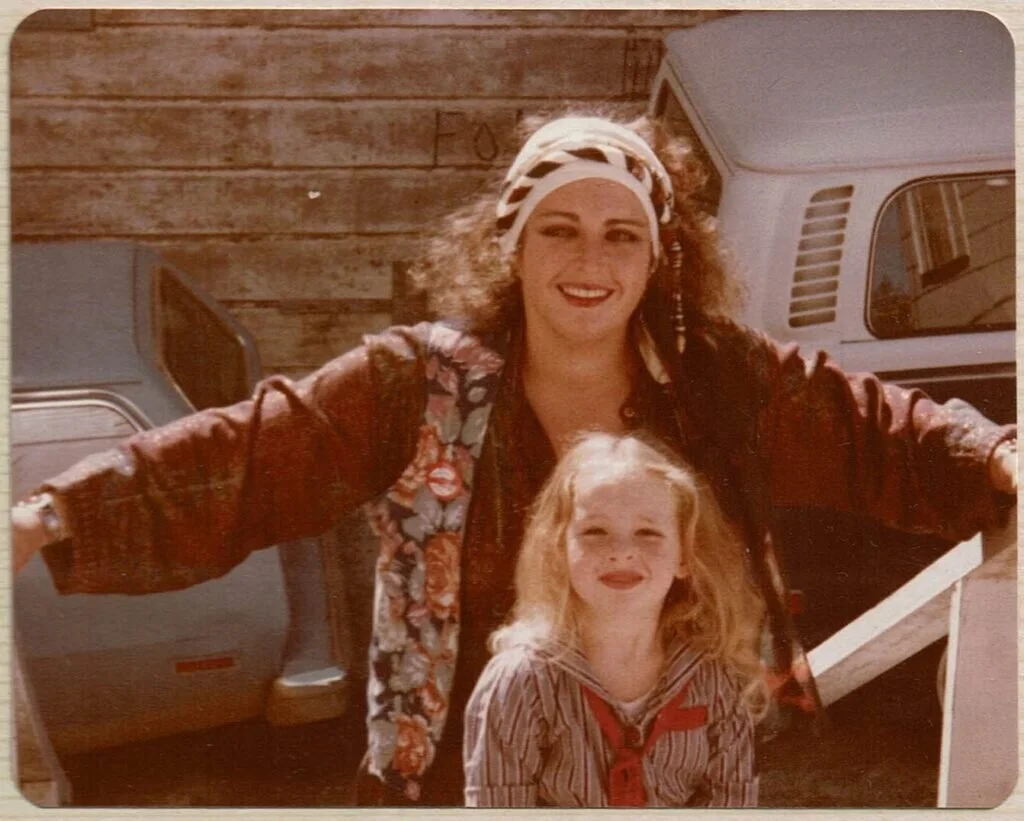

My folks also believed in hiding in plain sight. They dressed flamboyantly. Especially my dad, who sometimes looked like an early club kid. Their thinking was that if they drew attention to themselves, they would appear to have nothing to hide. Undoubtedly, racial privilege also played a role. A pretty white woman with a baby stroller wasn’t perceived as an obvious suspect. Had we been a family of color, things might have ended differently.

How did your mom pivot from serving hippies to caring for sick AIDS patients with cannabis edibles?

Alia Volz: Sticky Fingers launched in 1976, so the flower children had already gone to seed. New creative and activist movements were proliferating. My mom’s strongest client base was always with the LGBTQ+ community flourishing in the Castro.

When HIV-AIDS began to rampage around 1981, longtime friends and customers started getting sick. There wasn’t an effective pharmaceutical treatment until late 1995, so people were desperate for relief. Cannabis wasn’t going to cure AIDS, of course, but it eased some of the worst symptoms. Since my mom already had strong distribution channels within the LGBTQ+ community, the shift to palliative care came naturally.

High Herstory: There are many challenges growing up as the child of illicit business owners: mainly distancing yourself from peers who may put your family’s freedom at risk. What advice would you give parents in risky industries who are raising children, while also not being ashamed of their work?

Alia Volz: If your kids have to keep secrets in public, make sure they experience openness at home. Home should be a refuge where the child can let it all hang out and know they are loved, valued, and respected. My parents never disguised the nature of their business—or the fact that it was illegal. They were proud to work in cannabis. Yes, it was a secret, but there was no shame in it. Of course, it wasn’t always easy, especially during the Reagan-era drug war. I struggled to make friends, and there were moments when I wished we were a “normal” family. But honesty and intimacy within the cannabis community helped compensate for having to be guarded around other kids.

High Herstory: Your parents were spiritual. Do you have any cannabis spirituality practices of your own?

Alia Volz: Nope. Maybe it’s my small way of rebelling against my family.

Your new book, Home Baked: My Mom, Marijuana, and the Stoning of San Francisco is coming out in paperback on 4/20 of this year! What was the driver for you to come out with this book last year (in hardcover) during this changing time?

Alia Volz: Cannabis history is thick with hidden stories like the one I tell in Home Baked. The nature of prohibition meant that many of the crucial developments along the path toward legalization happened in secret. These are fabulous, epic stories! Who’s going to preserve them for posterity?

I chipped away at Home Baked for years. But it was during the lead-up to the 2016 election—when my home state of California legalized adult recreational use—that I shifted into high gear. In the debates I heard around legalization, I noticed that the legacy of HIV-AIDS activists in the cannabis world was being forgotten. This felt like a kind of erasure. In truth, we would not have today’s access without the labor and balls-out bravery of people who were literally fighting for their lives during the crisis. Having grown up embedded in that movement, I realized I held a vital piece of the story.

High Herstory: Are you reclaiming the word “outlaw”?

Alia Volz: My mom styled herself as a Robin Hood figure – someone who broke unjust laws to do what she believed was right. I do think there’s power in that. Living as an outsider forces you to think critically and develop your own moral compass. You have a different awareness of power dynamics than most people. You don’t look to society to dictate what’s right or wrong; those are personal decisions made according to your own values. Looking back now, I’m grateful I was raised to think for myself.